July 20th, 1969.

There were two things that happened that day. Technically many things happened that day, but there are two that are relevant to our story.

In Quebec, Bobby Pfeil’s squeeze bunt scored Ron Swoboda to put the New York Mets ahead 4-3 on the Montreal Expos at Parc Jarry, the predecessor to Olympic Stadium.

Above Earth, Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin landed on the surface of the moon.

If you’d asked a betting man at any point during the 1960’s which was more likely-a man landing on the moon, a feat not accomplished in all of human history, or the Mets winning more than a mere 60 games-they’d have told you to bet against the Mets.

Chavez Ravine, 1960s

Eleven years earlier, New York had part of its heart and soul ripped from it when the New York Giants and Brooklyn Dodgers departed jam-packed streets of the Big Apple and headed west for the howling winds of Candlestick Park at Hunter’s Point and the sunlit valley of Chavez Ravine in the shadow of the San Gabriel Mountains.

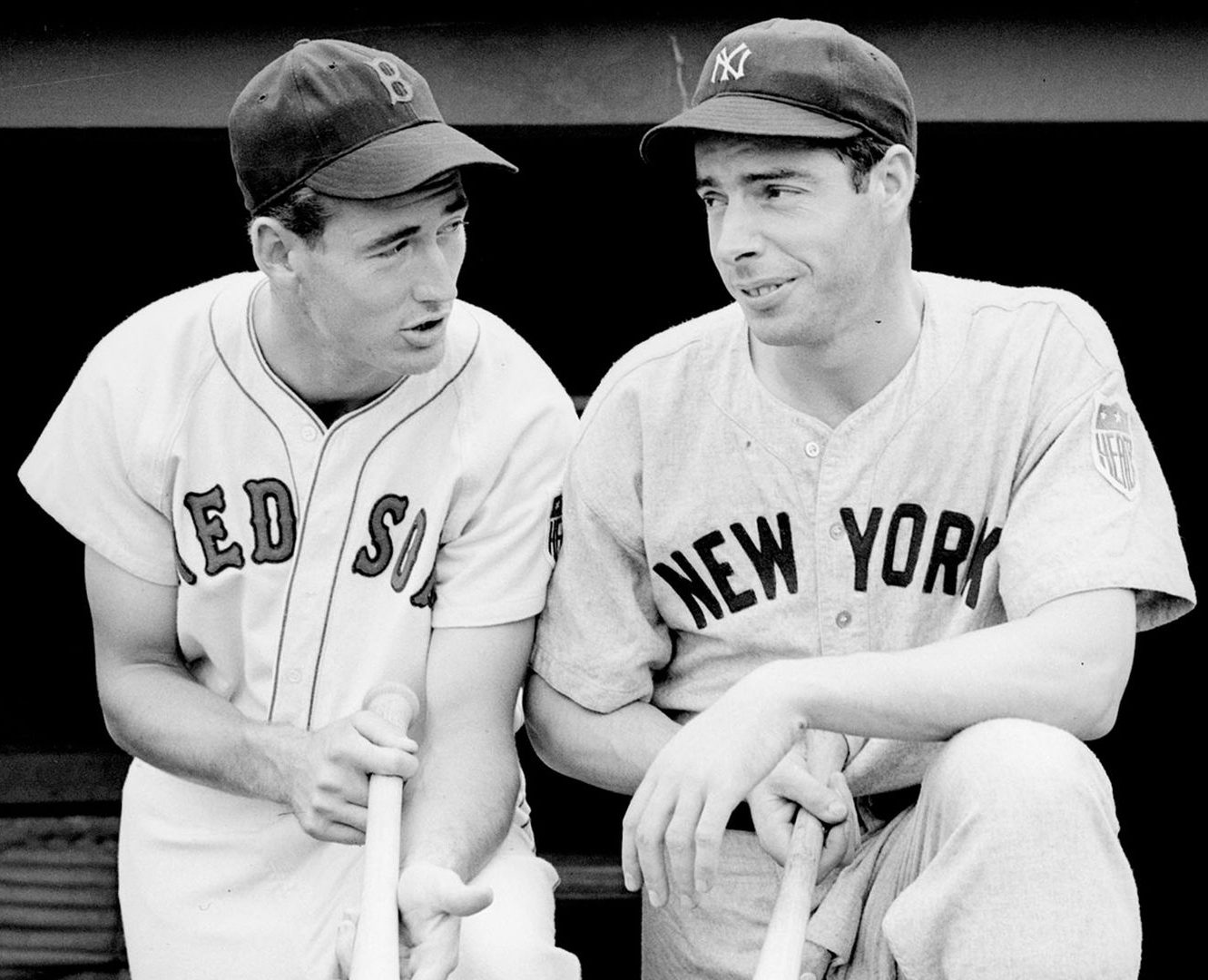

The Yankees, the Dodgers, and the Giants had duked it out for supremacy not only in the city of New York but all of major league baseball for the majority of its existence. The rivalries were entrenched, the hatred deep-seated. With the possible exception of the Athletics in Philadelphia or the Cardinals in St. Louis, New York’s trio of franchises were the greatest the sport had to offer.

Following the “Electric October” of 1947, the first televised World Series and often considered among the best series ever played, where Bucky Harris’s Yankees narrowly edged Burt Shotton’s Dodgers (Durocher was suspended), a team from New York played in the fall classic every year up until the Dodgers and Giants left for California in 1958, with the exception of 1948, where the Indians edged the Boston Braves in six games. Though that was the lone blemish in a decade of New York baseball dominance, Boston still lost, so the season was not a total loss for New York fans.

The Yankees beat the Dodgers four times and the Giants once in the Series that decade spanning from 1947 to 1957, winning five in a row at one point and seven overall. The Dodgers, long-time little brothers despite dominating the National League, finally gave the Yankees their comeuppance in another all-time series in 1955. The Giants, for their part, took home a ring in 1954 behind the spectacular play of Willie Mays.

By 1958, however, the inter-city rivalry was nothing but a memory, the Yankees’ closest geographical competition being the historically pathetic Phillies, who didn’t even play in the American League.

New York City baseball in the 1950s was a microcosm of the country as a whole. Emerging relatively unscathed from World War II (at least compared to the other major players in Europe and the Pacific), it seemed as if the United States could do no wrong that decade. Eisenhower’s highway program connected the country like a neural network, dispersing trade throughout state borders and improving prosperity for nearly everyone as the economy boomed. America was the greatest country in the world-New York was the greatest city in America-and the Yankees, Giants, and Dodgers were the greatest teams in baseball.

New York’s-and baseball’s-finest.

During the four years the Yankees presided as the sole team in New York, they managed to win two more championships, losing another in heartbreaking fashion, while the freshly christened Los Angeles Dodgers brought the World Series trophy to the West Coast for the first time in 1959.

One team, even one as great as the Yankees, wasn’t enough to satisfy New York’s thirst for baseball. At the request of Mayor Robert Wagner and following the rejection of his request for existing teams to move, attorney William Shea (sound familiar?) spearheaded an effort to found a third baseball league, known as the Continental League, and place a team in New York. The league had major traction, with owners set up and stadium locations set. Major League baseball, in response, set out to place expansion teams in the proposed cities. After some negotiating, they agreed to incorporate the Continental League teams as these expansion teams, provided that the teams provide their own funding for stadiums. This was a best-case scenario for Shea and the would-be owners. Rather than struggle as a fletching league in the shadow of a behemoth, they instead would be supported by the MLB, and Shea and Wagner’s ultimate goal of bringing a second team back to New York was realized.

They settled on the “Mets” after discarding names such as the “Skyliners” or the “Meadowlarks” (the personal choice of part owner Charles Shipman Payson, a former minority owner of the Giants who had opposed their move west). The name fit easily on sports pages and was quick to say. The working title for the team had been the “New York Metropolitan Baseball Club, Inc.”, and it seemed fitting. The colors of blue and orange were a natural fit as not only a homage to the Dodgers and Giants but as a tribute to the New York City flag as well.

The colors were the only thing that resembled the old guard of New York baseball when the Mets took the field at the decrepit Polo Grounds for the first time in 1962. Skipper Casey Stengel, the manager for many of those legendary 1950’s Yankees teams, was instead saddled with what is often considered to be the worst roster in baseball history.

Instead of Snider, Mays, and Mantle vying to be the best centerfielder in the city, fans watched the beloved “Marvelous Marv” Throneberry and his .244 batting average. Instead of duels between Don Newcombe and Whitey Ford, the Mets trotted out a pitching staff where just one member-Al Jackson-managed an ERA under 4.50. The team, as a whole, saved 10 games on the year. A good closer in today’s game saves more games than the team won for the entire year-40.

The team’s two best players were centerfielder and eventual Hall of Famer Richie Ashburn in his final season, and slugger Frank Thomas (not that Frank Thomas), who manned left. And while they didn’t recapture the speed and grace of their fore-bearers in the uniquely shaped confines of the now dilapidated Polo Grounds, their incompetence did lead to what is often considered one of the best stories in baseball history.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/46361492/1962_Mets_Roger_Craig_Ralph_Kiner_Elio_Chacon_Louis_Requena_Sporting_News_via_Getty_Images.0.0.jpg)

Pitcher Roger Craig and shortstop Elio Chacon being interviewed by the legendary Ralph Kiner.

The 1962 Mets had a problem. Well, in reality, they had many problems, but only one that is pertinent to this story.

A characteristic of a bad team is a lot of errors, and the Mets were no different. They were especially prone to the embarrassing kind, with fielders running into each other an dying quail dropping in between three guys who could have easily caught it. Ashburn and Thomas were having particular issues with Venezuelan shortstop Elio Chacon, who spoke no English. A soft pop-up would float between them, where Ashburn would range over and yell “I got it, I got it”, in traditional baseball vernacular. Chacon, of course, speaking no English, had no idea what Ashburn was going on and on about, and this miscommunication led to an inordinate number of collisions and drops.

The seasoned Ashburn had made his way as a quick, intellectual ballplayer, and soon thought of a fairly obvious solution to the problem. Ashburn called a meeting between him, Chacon, and Thomas, and explained that they were now going to yell “¡Yo la tengo!” -Spanish for “I got it”-on fly balls in their area as to avoid the Three Stooges routine they had been employing thus far.

This seemed a fine solution, simple but effective.

The next day, however, the Mets learned that they were more subject to Murphy’s Law than Occam’s Razor.

The exact scenario for their new plan unfolded as a soft fly ball was lifted to shallow center. “Yo la tengo, yo la tengo” hollered Ashburn, and Chacon peeled off on cue as Ashburn settled under what should have been a routine can of corn. However, while the 170 pound Ashburn had avoided a collision with the 160 pound Chacon, he was instead walloped by the 6’3, 200 pound Thomas, who, speaking no Spanish and having missed the briefing earlier, had careened in from left field like a runaway train.

As the diminutive Ashburn and hulking Thomas picked themselves off the ground, a confused Thomas asked the irritated Ashburn: “What the hell is a Yellow Tango?”

Casey Stengel in some new threads.

The Mets fared better in 1963, only because they literally couldn’t have been any worse. It took them until 1966 to crack 60 wins, with poor old Casey Stengel, used to the dominance of the crosstown Bronx Bombers, helplessly asking “Can’t anybody here play this game?” as he failed to top 53 wins in a four year tenure as manager.

Despite the fact that the Mets had replaced two of baseball’s most successful franchises with the worst stretch of professional baseball in recent memory and perhaps ever, they were the darling of New York City. It was amazing-amazin’, really. New Yorkers, long beleaguered for their short tempers and high expectations, loved the Mets nonetheless. Fans turned out in droves, their attendance consistently ranking in the top ten.

Historical ineptitude creates a unique environment for stories like the time a fan called the newspaper to ask the score of the game that day. The newspaper informed him the Mets had scored an incredible 19 runs. After a pause, the fan asked “Did they win?”

In 1966, they selected catcher Steve Chilcott, who never made the majors, as the first overall pick, one spot ahead of Reggie Jackson.

1966 was a big improvement. At 66 and 95, they were just “regular bad” and not “historically bad”.

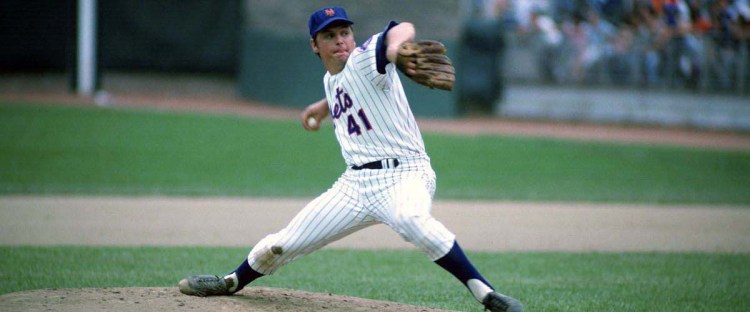

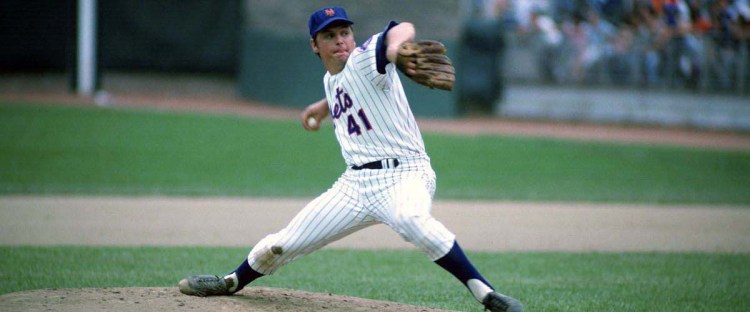

In 1958 California had robbed New York of baseball. Nine years later, the the debt was partially repaid in the form of the brilliant debut of USC star Tom Seaver. In perhaps the Mets first stroke of good luck ever, they were granted the rights to sign him in a lottery despite the Braves selecting him initially due to a dispute about drafting Seaver after the USC season had already started. Though the Mets slipped back down to 61-101, Seaver’s brilliance finally gave them their first true star player.

Though it was easy to poke fun at the Mets misfortunes, there was a glimmer of hope beneath the surface. In the past few years, they’d signed promising southpaw Jerry Koosman, flamethrowing righty Nolan Ryan, and speedster Cleon Jones. They’d flipped Jim Hickman and Ron Hunt for Tommy Davis, who hit .302 for them and was subsequently traded for Tommie Agee.

The 1968 lineup was completely toothless, resulting in a dismal OPS+ of 79. Yet the Mets had their best season ever on the backs of a pitching staff that was terrific throughout. In a reversal of that nightmarish staff on the 1962 squad, Ryan was the only starter with an ERA above 3, and he barely eclipsed it at 3.09. Seaver and Koosman, at 23 and 25, were the league’s best duo and among the greatest righty-lefty combos ever. The Mets had become something more than lovable losers-they were downright watchable, if still incredibly frustrating. The change was palpable. Instead of expecting a loss and being thrilled to stumble into a win, it was disheartening to watch the lineup blow a gem from the rotation. Suddenly, the Mets had expectations, no matter how tempered they might be. For the first time ever, they didn’t finish last in the National League. Instead, they finished 9th. Out of 10.

The Mets still stunk. Seaver sure didn’t.

1969 got off to an inauspicious start. The Mets, despite their improvement in 1968, had still only eked out 73 victories. What’s more, attitudes around the country had stiffened throughout the 60s. When the Mets were inaugurated in 1962, the country was still riding high on the optimism and success of the 50s. It was fun to watch the lovable losers, root for the little guy, and hold an almost morbid fascination with the team that seemed to find new ways to lose every week.

By 1969, the glum hopes of the Mets matched the attitudes of a weary country battered by a decade of assassinations, civil unrest, and war. It was no longer fun to watch a team whose perennial failures mirrored day to day life a little too closely. Sports, and entertainment in general, serve as crucial parts of a society as an outlet from the suffering of the world. It was one thing to chuckle at the comical ineptitudes of a clueless Frank Thomas bulldozing Richie Ashburn, or a fan so jaded he was incredulous the Mets could win a game in which they posted 19 runs. It was another to have them serve as a reminder of the very same frustrations Americans were trying to escape.

They’d lost Dick Selma, who logged a sterling 2.75 ERA in ’68, in another expansion draft to the Padres before the season. They stumbled out the gate, winning just three of their first ten games.

Things weren’t better by the end of May, with the Mets still five games under .500. Facing the equally hapless Padres, the revamped lineup managed a meager two runs as they were shut down by Al Santorini, who twirled a complete game. It looked to be business as usual in Queens, with fans growing tired of the act.

The next day, May 28th, had Koosman on the bump facing Clay Kirby. The two were deadlocked in a pitchers duel from the first pitch, Koosman with the ball on a string. The Padres couldn’t touch Kooz, who just got stronger as the game went on. With 11 strikeouts through seven innings, Koosman trotted out for the 8th and promptly struck out the side, all swinging.

The lineup, however, looked to be the same old Mets. They managed seven hits against Kirby (compared to just four given up by Koosman), a 20 year old rookie in the midst of a 20 loss campaign, but zero runs. He even gave up three walks as the Mets got runners in scoring position with no outs three separate times and failed to capitalize.

The Mets went out with a whimper in the bottom of the ninth, leading manager Gil Hodges with a decision to make. Hodges, who sparred with the Yankees as part of the heart of the legendary Brooklyn Dodgers lineups in the 1950s, had actually played 11 games for the Mets back in 1963, struggled to keep his average above the Mendoza line, and promptly was traded so he could retire and manage the Washington Senators. He took over in ’68 and was thought of somewhat of a miracle worker for engineering a 12 game improvement and a developing a legitimately excellent pitching staff. Hodges stuck with his guns and sent Koosman out there for the tenth.

Roberto Pena led off the inning with a clean single to center, but Koosman didn’t flinch. He got Cito Gaston to pop-up and took care of it himself, then induced a lineout to Agee in center. Padres manager Preston Gomez was the fist to blink as he pinch-hit Ivan Murrell for Kirby. Koosman backwards K’d him, giving him 15 on the day.

Hodges pinch-hit for Koosman in the bottom of the tenth, but the Mets were again fruitless in their endeavors at the plate. Tug McGraw came out of the bullpen and blanked the Padres in the top of the 11th. Billy McCool (real name), who had stymied the Mets in the 10th, came back out for San Diego in the bottom of the inning. Cleon Jones bounced a routine grounder to short, but shortstop Tommy Dean flubbed it. McCool settled and struck out Ed Kranepool, but Gomez lifted him for Frank Reberger anyways. Swoboda singled to center, with Jones hustling from first to third. Jerry Grote was intentionally walked, bringing Bud Harrelson to the plate. In years past, Harrelson would have grounded into a double play and ended the inning. After all, that’s what the Mets did. They could never seem to stay out of their own way, shooting themselves in the foot at every possible juncture. After all, they could barely beat the expansion Padres, who would go on to finish the season with just 52 wins of their own.

But this team was different. No longer were they content to be the laughingstock of the league. No longer were they complacent enough to waste stellar performances like the one Koosman had turned in that day. That showed when Harrelson ripped a clean single up the middle, scoring Jones, and mercifully ending a game which they should have won five times over.

Jerry Koosman was Seaver’s equal in 1969.

That was the start of an eleven game winning streak for the Mets, unheard of in Queens. Excitement was starting to build in the city.

Those boys are really something, eh? They’re amazin’.

The team had stepped out of the shadow of the Yankees, who were stumbling through their most miserable half-decade since they traded for Babe Ruth. American icon Mickey Mantle’s hard lifestyle had reduced him to a shell of his former self, and he’d finally hung ‘em up after 1968. All anyone could talk was the Mets-the Amazin’ Mets.

The boys stayed hot as the weather grew muggy and their jerseys began to stick to them in the humid summer months. They kept playing well all the way up until July 20th, where they beat the Expos in Montreal, Armstrong and Aldrin went for a joyride on the moon, and they were given a much-needed week of rest at the All-Star break. Seaver, Koosman, and Jones were selected for the game.

The Mets’ own Cleon Jones right there with Bench, McCovey, and Aaron.

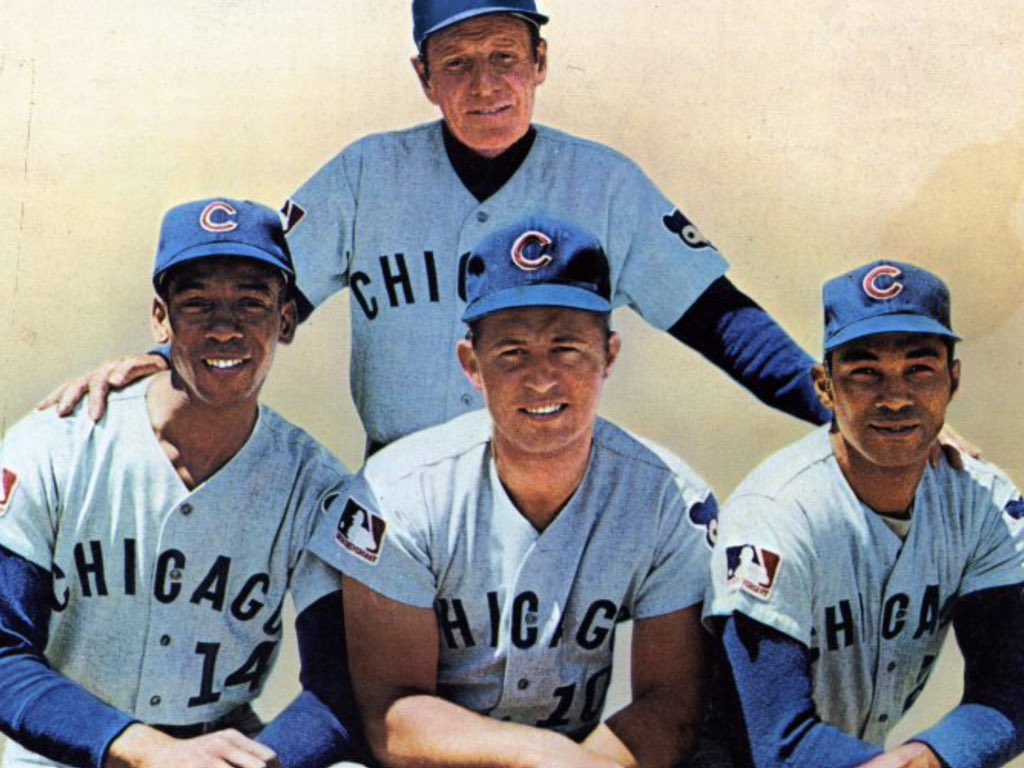

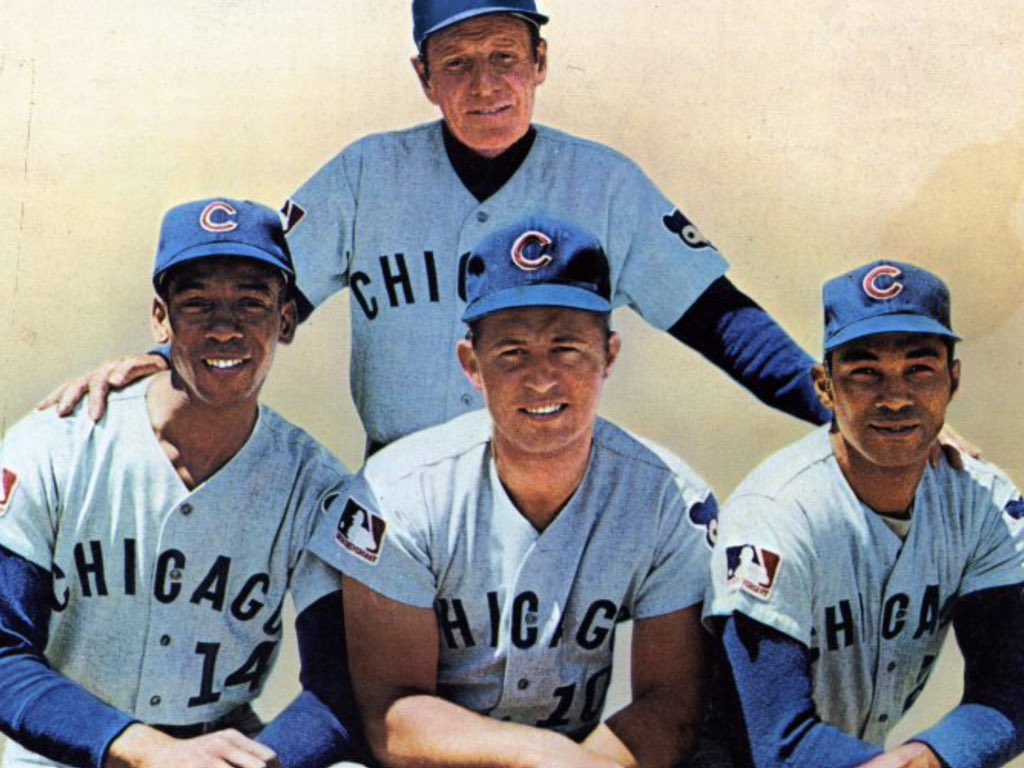

The Mets stood at 53-39 at the break, easily their best record at this point in the season in team history, but still five games behind the 61-37 Cubs, led by their own dynamite pitching staff and featuring a lineup with three Hall of Famers (Ernie Banks, Billy Williams, and Ron Santo). The Cubs featured a pair of familiar faces-Jim Hickman, who had endured the dreadful Mets teams before becoming a part of the sequence of trades that would land them Agee, and Dick Selma, who had been acquired by the contending Cubs from the rudderless Padres.

When they returned from the break, they appeared listless, staggering out to a 2-5 start where they got smoked 16-3, then 11-5 in a doubleheader in Houston on July 30th.

Same old Mets, I guess.

The Mets started Gary Gentry in the nightcap, who walked six guys and was gone before he could finish 3 innings. Ryan came in out of the bullpen to relieve him and promptly gave up a double to Johnny Edwards. Following the ego bruising of game one and with game two out of hand before the third, Cleon Jones didn’t feel much need to hustle after Edwards’ double to left, taking his time fielding the ball and relaying it to the infield.

In a moment that play-by-play broadcaster Ralph Kiner would extol for decades as the one that defined the season, Hodges limped out of the dugout and took a long, meticulous walk out to Jones in left to personally lift him for Swoboda. It was humiliating for Jones. Rather than yanking him from the dugout, or having one of the assistant coaches go out there, Hodges sent a clear and personal message about hustle. We are not those Mets, and you will not play for us if you are that type of player.

Gil Hodges-stud first baseman, wily manager, and Daniel Craig doppleganger.

The Mets were on fire, again. They won 20 games in August as the pennant race heated up. While the National League west was a dead heat, with five teams within five games of each other jostling for a playoff berth and only the lowly Padres out of contention 35 games back, the East was a two-horse race between the Cubs and the Mets. And despite their red-hot August, the Cubs had matched them, going on a tear of their own and leaving the standings exactly as they had been at the break, with the Mets five back.

Saying the Mets would need a “miracle” to make up five games in a month would be a stretch, but with the way the Cubs were playing, it didn’t seem like much of one. These were the Mets, after all-no matter what they did, it seemed like they always got the short end of the stick. They’d played with their hair on fire for a month and it was as if they had been running on a treadmill-they were no closer to catching the Cubs than they had been a month ago.

A one-month playoff race seemed to favor Chicago in every way. The Mets stars were still greenhorns-not one of their starting lineup was over 26. Seaver and Ryan-two of the greatest pitchers to walk the Earth-were just 24 and 22 respectively, and Ryan wasn’t even in the rotation full time. Hodges had managed the Senators for five years, and they had always been lousy. The Mets had never even finished a season over .500.

The Cubs in contrast, were composed of grizzled veterans. Banks, Santo and Williams were already legends of the game. Though Banks was on the decline, he was still an effective player and Santo and Williams were still in their prime. Their rotation, led by Jenkins and Selma, was more seasoned that New York’s, yet still young and looked to have plenty of juice for the upcoming playoff run. Instead of the unproven Hodges, the Cubs were managed by old war dog Leo Durocher, whose wisdom was matched only by his temper.

The Mets and Cubs were set to finish the season in a two-game series at Wrigley. It certainly looked like it would be the decisive series of the season.

Durocher with the heart of his lineup. The Cubs matched the Mets win for win in August.

The much anticipated season-ending series ended up being a dud. While the Mets roared through the finish line, outdoing themselves by winning an incredible 23 games in the month of September, the Cubs blew a tire while Durocher blew a gasket, and they limped into October having won a paltry 11 games in September. The teams split the series, the Mets winning an even 100 games and finishing a comfortable eight games ahead of the Cubs. For a team where it had been an accomplishment to not lose 100 games just three seasons prior and had only managed the feat twice before this season, it was exactly as they say-a miracle.

Yet another challenge faced the Mets as they secured their first ever playoff berth. The latest round of expansion, increasing the number of teams in Major League Baseball to 24, had led to a format change in the playoffs. Instead of the top team in each league going on to the World Series, 1969 would be the first year ever for the National League Championship Series, where the Amazin’ Mets would take on the old guard of the National League, the ageless Hank Aaron’s Atlanta Braves.

The Braves were another veteran team, led by Hall of Famers Aaron and Orlando Cepeda, and backed by the reliable Felipe Alou and Clete Boyer. Joe Niekro was their ace, six years Seaver’s elder but a longtime rival of his in the decades to come.

Still no one gave the Mets much of a chance. The Braves had emerged from the bloodbath in the NL West, while the Cubs’ collapse had practically handed the division to the Mets. The Braves featured eventual home run king Aaron, who was well on his way to passing the Babe, while the entire Mets infield had failed to hit 20 dingers combined. Cleon Jones finished third in the National League in batting average at a .340 clip, but the only other player to clear .300 was part timer Art Shamsky off the bench.

Game one was knotted at four apiece until Aaron reminded Seaver that this was still his league, homering off him in the bottom of the seventh to put the Braves ahead by one. Niekro faltered in the eighth however, with a rally led by Jones and Shamsky eventually getting out of hand when an two errors on J.C. Martin’s single leading to a five run inning and the Mets running away with it.

Koosman was uncharacteristically sloppy in Game two, but it hardly mattered as Atlanta starter Ron Reed was even worse. Agee, Ken Bosewell, and Jones homered as New York boat raced them 11-5.

In a repeat of that fateful day in July, Gary Gentry got off to a rocky start before he got the quick hook from Hodges for Ryan, who went the distance while Agee’s seven total bases paced the offense to a 7-4 lead. And just like that, the Mets were in the World Series.

Completed in 1964, no one expected Shea Stadium to host the World Series within the decade.

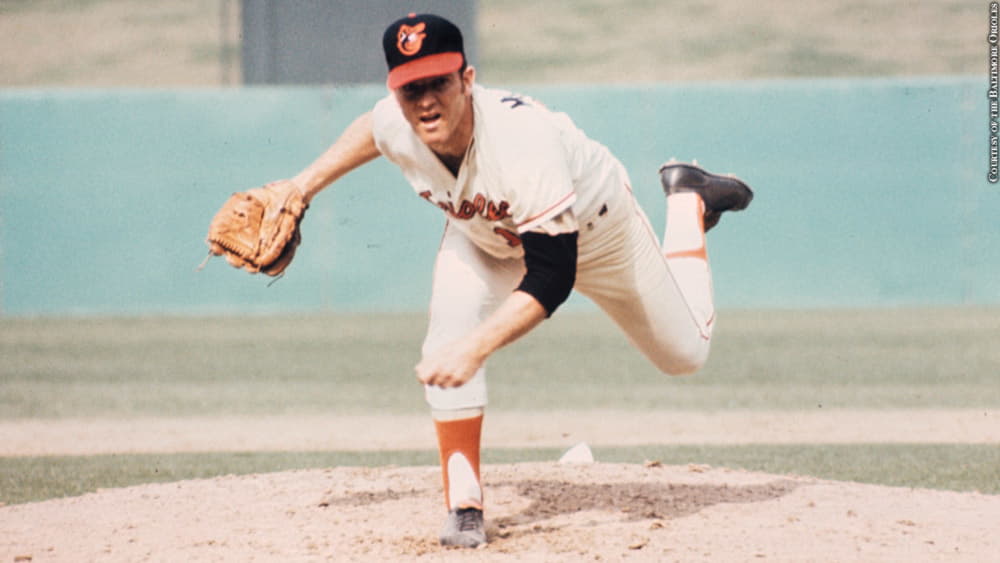

No one could dismiss the Mets now, especially after they had made swift work of the favored Braves. Yet the odds were still stacked against them, as they faced the 109-win Baltimore Orioles.

The Mets weaknesses were obvious. They lacked power-only Agee managed more than 15 home runs, with 26, as well as offense in general. And they were inexperienced, brutally so. Most of the guys had no experience being on a winning team, much less a playoff one.

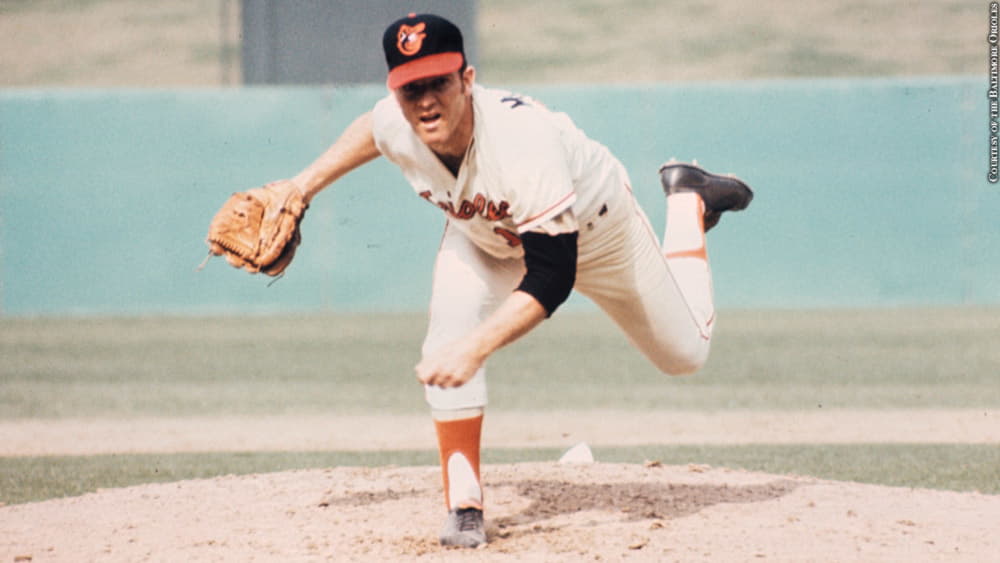

The Orioles, in contrast, had plucked the crown from the suddenly hapless Yankees and had staked a claim as the American League team of the ‘60s, winning it all in 1966 and putting together impressive campaigns in ’68 and of course 1969.

The lineup was fearsome, featuring inner-circle Hall of Famers like the Robinsons-Frank and Brooks, respectively. Speedy Paul Blair in center had a 20-20 season, and even second baseman (and future Mets manager) Davey Johnson, though four years ahead of the time he would hit an astounding 43 home runs despite never hitting more than 18 in any other season, was a dangerous ringer in the lineup. First baseman Boog Powell crushed 37 home runs and batted .307, finising second in the MVP. In fact, Brooks Robinson, in a down year, was actually their worst starter by OPS+. This mattered little in the playoffs. He was still Brooks Robinson.

The Orioles rotation was no slouch either. Mike Cuellar, Dave McNally, and another longtime Seaver rival in Jim Palmer headlined one of the finest rotations in baseball. They were supported by a terrific defense, anchored by the “Vacuum Cleaner” Robinson at third, often considered among the greatest defenders ever. Johnson, shortstop Mark Belanger, and Blair also took home Gold Gloves giving them an astounding four Gold Glove winners on one defense. The press was also impressed with the job the then-unknown rookie skipper Earl Weaver had done in his first full season.

Most pundits had the Orioles winning fairly handedly, per usual. The plucky Mets were fun, they penned in their sports columns. But the fairy tale had to end sometime.

If there was a game for the Mets to win, it would be Game one, people agreed. After all, Seaver was the best in the business, and as great as Cuellar was, no one could match Tom Terrific.

As it turns out, the one optimistic prediction for the Mets fell through. Seaver was roughed up, taking it on the chin while Cuellar was masterful in a one run complete game.

That settles it, disappointed fans gloomed. Don Buford’s first inning homer off Seaver had set the tone for the game from the outset, and maybe the entire series.

Cuellar, McNally, and Palmer felt they could go toe-to-toe with Seaver, Koosman, and Gentry.

Game two was a matchup of ace southpaws Koosman and McNally. Each came out the gate tossing zeros. Frank Robinson hit a deep fly ball in the second, but Swoboda settled under it. Then in the third, Belanger hit a deep shot to center that looked like it had a chance to go until Agee snagged it short of the wall.

McNally got himself in a spot of trouble in the 2nd, walking Donn Clendenon, then inducing a fielder’s choice from Ed Charles before bouncing a wild pitch to send Charles to second. Jerry Grote flied out to end the threat.

The Mets struck first in the fourth. Clendenon, who seemed to see the ball well coming out of McNally’s hand, boomed a deep shot to the power alley in right. When the ball cleared the wall, he had himself an opposite field home run and the Mets were in the lead.

Koosman was dealing. He cruised through the sixth with a clean sheet-though he had walked Johnson in the second, there was still a goose egg in the H column for the Orioles.

Unfortunately for the Mets, McNally had settled quickly after the Clendenon homer. He made quick work of Swoboda, Charles, and Grote, then struck out the side in the fifth.

Paul Blair singled to lead off the seventh. Koosman carefully picked his way through Frank Robinson and Powell, leaving Blair at first with two outs while facing Brooks Robinson. Finally having cracked through Koosman’s shell, Baltimore decided to press their advantage as Blair jumped for second and slid in ahead of the throw. Brooks rose to the occasion and poked a single to center. The fleet-footed Blair was going on contact, and Agee had no play to make at the plate. It was tied up at one apiece.

It looked as if the Mets were once again to waste a great outing by Koosman. If it bothered him, he didn’t show it, with a 1-2-3 eighth. With two outs in the top of the 9th and McNally cruising, the game looked to be headed for extra innings at best and a walk off victory for the Orioles at worst. However, Ed Charles, Jerry Grote, and Al Weis strung together three straight singles to left and put the Mets back on top. Hodges put his faith in his co-ace, refusing to pinch hit for him so he could go out and finish the game in the bottom of the ninth.

After Koosman bounced into a routine 6-3, he took the mound in the 9th and retired Buford and Blair before walking Frank Robinson and Powell. Hodges’ leash was long, but not infinite. Ron Taylor came in, and in a tense at-bat with Brooks Robinson, induced a grounder to Ed Charles at third, who nabbed him at first by a step to close it out.

Game three was a yawner. Palmer got the nod for Baltimore, while Gary Gentry toed the rubber for the Mets. The Mets roughed up Palmer for five runs in six innings, while the Gentry-Ryan duo combined for a shutout, with Gentry picking up most of the legwork this time.

Game four was a matchup of the opener, but Seaver had his good stuff this time. Once again, Clendenon staked his starter to an early lead, and Tom was untouchable through eight. Eddie Watt relieved Cuellar after seven terrific innings, and didn’t miss a beat.

In the ninth, Seaver had to go through the heart of the lineup to finish the game. He got Blair to fly out, but Frank Robinson and Powell singled, sending Robinson to third. Now it was Brooks Robinson again, and he came through for the Orioles once more, clubbing a sinking liner to right. Swoboda-long favored by Hodges for his defensive prowess despite his meager abilities at the plate-made a terrific diving catch to record the out, but had no play to make as Robinson easily tagged and scored to tie the game. Watt gamed his way through the middle of New York’s lineup and it was on to extra innings.

Hodges rode his ace yet again-he seemed to only use relievers for Gentry, and usually only Nolan Ryan if anyone. Hodges was prepared to live and die by his young aces.

Seaver was shaky in the tenth, but gathered himself to strike out Blair and get out of the jam. Dick Hall came in for the Orioles to try to extend the game, but a funky double by Jerry Grote that was more hustle and borderline error by Don Buford got Shea rocking. Al Weis was intentionally walked to set up the double play. Thirty-two year old backup catcher J.C. Martin, who had batted a measly .209 on the year, stepped up to pinch hit for Seaver as Orioles pitching coach George Bamberger (Weaver had become the first manager to get ejected in the World Series arguing balls and strikes in the third) bought in Pete Richert.

Martin laid down a bunt and lumbered towards first. Richert scooped it up and whipped the ball over to first, where Davey Johnson was covering the bag. Richert’s throw, however, pegged Martin in the wrist and pinch runner Rod Gaspar came around to score the winning run.

The Orioles claimed that Martin was running too far inside the first base line and therefore had interfered with Richert’s ability to make a play on the ball, meaning he should be ruled out and Gaspar sent back to third, but they were overruled.

Koosman and ace reliever Nolan Ryan. Few expected he would be baseball’s all time strikeout king.

Game five at Shea was a madhouse. Here were the Mets, New York’s Mets, Queens’ Mets, up three games to one in the World Series with a chance to bring home a trophy. It would have seemed like a sick joke just two years ago, the team dredged in a cellar many felt they would never get out of.

It was Koosman and McNally once again. This time the Orioles were the ones who drew first blood, as McNally shockingly belted a two-run homer in the third, and Frank Robinson followed suit with a solo shot of his own three batters later.

Controversy arose in the sixth, as McNally bounced a slider in the dirt at the feet of Jones, which then skipped all the way into the Mets dugout. The Mets argued that it had hit Jones in the foot and held up a ball scuffed with shoe polish to prove it-the Orioles argued that it had merely bounced in the dirt.

Years later, Ron Swoboda would admit that the wild pitch skidded into the dugout and knocked over a bucket of balls. It was impossible to tell which one was the game ball, and Hodges grabbed a ball with a black smudge on it and used it as Exhibit A in his case. At any rate, whether that was the game ball or not, the umpires granted Jones first base. McNally, Weaver, and the Orioles were furious.

It proved consequential as Clendenon followed Jones and continued his hot streak by ripping a bullet over the left field fence. The stadium exploded as the Mets pulled within one.

Koosman set down the side in order in the top half of the seventh. It was getting tight now, with just three innings to go and the 8, 9, and 1 spots due up.

Veteran journeyman Al Weis was due up to lead off the bottom of the seventh. Another guy who flirted with the Mendoza line before it had even been invented, Weis was in the game as defensive specialist. Though he’d hit surprising well in the playoffs, everyone expected McNally to mow down the bottom of the lineup in short order. Weis shocked the world when he smacked a McNally fast ball high and deep to left, sailing over the wall into the shallow bleachers beyond, sending Shea nuclear. The stadium roared as the unlikely hero tied the game up.

Curt Motton pinch-hit for McNally, taking him out of the game. He grounded out weakly to Harrelson as part of a 1-2-3 inning for Koosman.

Eddie Watt was back in for Baltimore in the bottom of the eight, and promptly gave up a double to Jones, igniting the fans once again. The ever dangerous Clendenon rolled a grounder to third that failed to advance the runner. Then, Swoboda-another defensive specialist in a big moment at the plate-laced a double in the left-center field gap, easily scored the speedy Jones and putting the Mets just three outs away from the unthinkable. After an error by Powell bought them an insurance run, Koosman trotted back out for the ninth, facing the troublesome heart of the lineup one more time.

Frank Robinson, Boog Powell, and Brooks Robinson was about as intimidating a 3-4-5 combo you’ll find in baseball history outside of the Ruth-Gehrig-Literally Anyone With a Pulse division. Koosman had to go straight through them to achieve what was once impossible but clearly within reach-all they had to do was go out and take it.

Koosman walked Robinson to start, not risking anything with the feared slugger. Boog Powell grounded into a fielder’s choice. Chico Salmon came in to run for the sluggish Powell. Now, Brooks Robinson. A fly ball lofted to right, easy work for the steady Swoboda. Koosman needed just one more out from the sneaky powerful Davey Johnson. After a couple of off-speed pitches that Johnson didn’t bite at, Koosman came into the zone with a fastball. Johnson swatted it deep to left with good contact, as Cleon Jones drifted towards the warning track. But no further-he settled under it and squeezed the final out a few feet in front of the warning track, as jubilant fans stormed the field. The Mets, who had been born into the decade as lovable losers during Kennedy’s “Camelot” America, had emerged at the other side of the decade as champions in a much different country. A tired, worn, America, a world-weary America looking for hope somewhere. And they found it in the Miracle Mets.

Amazin’!

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/46361492/1962_Mets_Roger_Craig_Ralph_Kiner_Elio_Chacon_Louis_Requena_Sporting_News_via_Getty_Images.0.0.jpg)

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/63352945/usa_today_12441403.0.jpg)

![CHICAGO - APRIL 17: Tim Anderson #7 of the Chicago White Sox throws his bat as he reacts after... [+] hitting a two-run home run in the fourth inning against the Kansas City Royals on April 7, 2019 at Guaranteed Rate Field in Chicago, Illinois. (Photo by Ron Vesely/MLB Photos via Getty Images)](https://thumbor.forbes.com/thumbor/960x0/https%3A%2F%2Fspecials-images.forbesimg.com%2Fdam%2Fimageserve%2F1143397623%2F960x0.jpg%3Ffit%3Dscale)